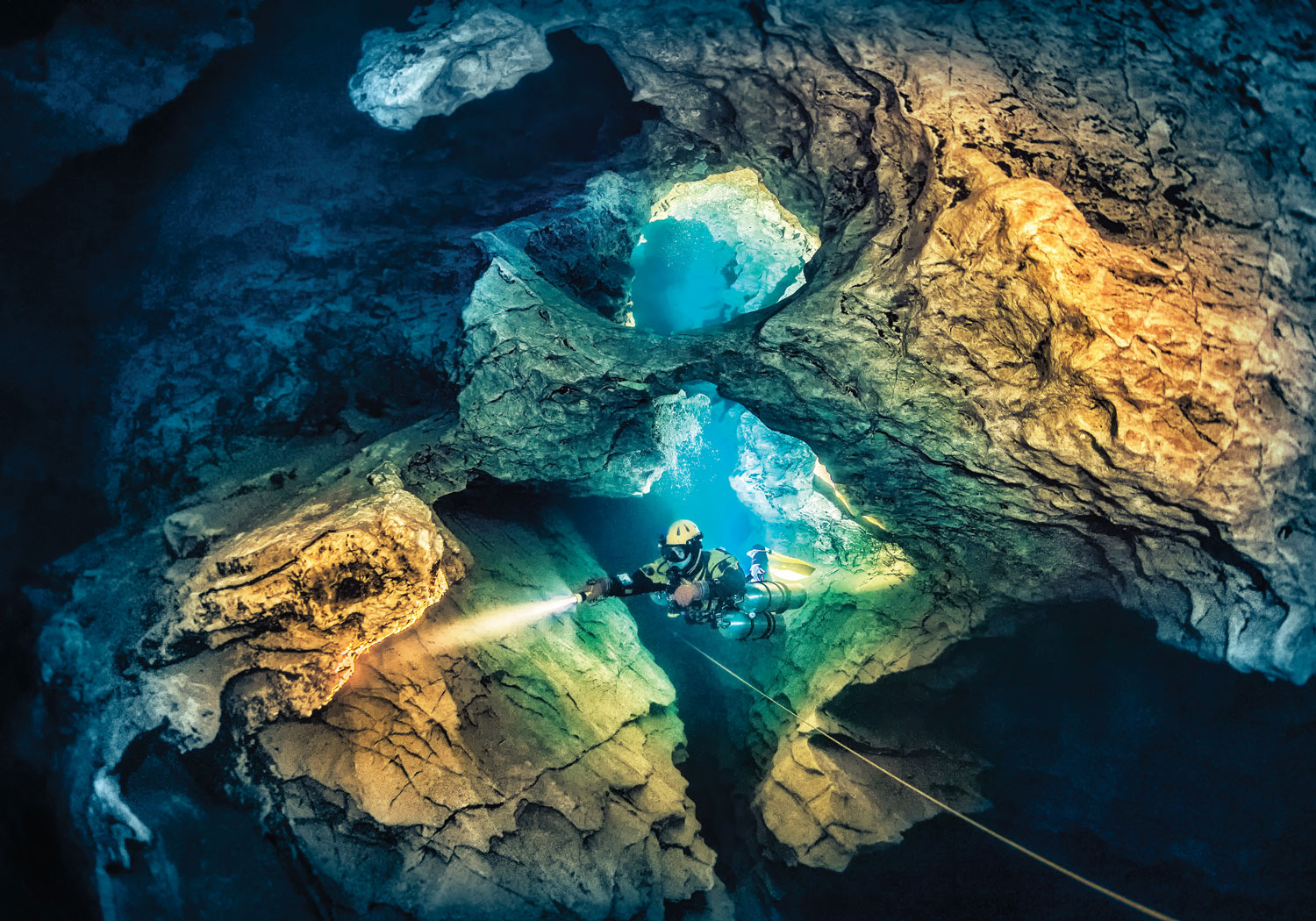

Prepared diver

Situational Awareness: The Ace in the House of Cards

‘Situation awareness (SA) is the ability to perceive data from the environment around us, to make sense of that data to create information, and then look to see how this information along with previous experiences will help us predict the future more accurately. If we think about these three steps – perceive, process, project – we can see what SA is and how to improve it.

- Perceive – this is based around our sensory systems, especially our eyes as they have a huge influence over what we believe to be the real world. There are so many visual illusions out there which highlight this. To improve our SA, we need to know where to ‘look’ for data e.g., increase the frequency we look at critical information like depth, bottom time or decompression overhead, site location, exits etc. This where effective dive briefings can help.

- Process – this is based around making sense of what we have perceived. This process is informed by previous experiences. If we haven’t seen something before, or seen the outcome, we shouldn’t be surprised when we don’t understand what we are sensing right now. Therefore, to build SA, we need to build experience in a variety of environments.

- Project – this is based on our previous experiences but isn’t about what it means now, but rather, what is going to happen in the future. Again, this is where experience is so important. However, this experience doesn’t have to be direct, you can learn from others’ stories and accounts.

More mistakes are made because of inadequate SA and ‘good decisions’ than good SA and ‘poor decisions’, hence the need for effective SA. You can’t pay MORE attention, but you can make sure you point it in the right direction.’

Gareth Lock, Owner/Director of The Human Diver, delivering online and face-to-face human factors education in diving.

Play chess? Observing current moves and anticipating the coming moves is the key to mastering the game. This is a good analogy for what Situational Awareness (SA) is all about: a tactical short-term cognitive process. In diving, SA is the process of perceiving environmental elements and events underwater, assessing their significance, and projecting their future effects as an asset, a risk, or a peripheral consideration. Since SA is a foundation for successful decision-making, a lack of it leads to human error, one of the primary casual factors in diving accidents.

Most of divers’ time underwater is split between training and non-training dives. The goal of training dives is to develop new skills in order to reinforce and gradually move through each and every level of our House of Cards pyramid. Situation Awareness takes the place at the very top of this pyramid: Only a diver with solid foundations (breathing, buoyancy, trim, propulsion, team awareness) has the free mental capacity to turn their attention to their surroundings. Once these foundations have been acquired during initial training, further training becomes more safety oriented and aims at building dependable responses to a number of what-if scenarios: what if one runs out of gas, what if one has an equipment failure, what if the team gets separated, what if one misses a decompression stop, what if there is a loss of visibility, and so on. The trained responses to all these potential situations are the output of a mental model based on the collective experience that the diving community has developed over decades. The underpinnings of this model were first described in the booklet “Basic Cave Diving: A Blueprint for Survival” (1979) by legendary cave explorer Sheck Exley: developing knowledge, future responses, and training based on past human errors and accident analysis.

The value of this long-term model is to prevent divers from being overwhelmed by information – instead of having to come up with a solution to a problem under time pressure, a diver can to rely on a set of trained responses: one situation equals one action. The downside however is that these responses need to be drilled repetitively to become automatisms. Some training agencies reinforce this by requiring their divers to undergo a formal reevaluation process at regular intervals. Where this is not the case, many instructors will still advise their students to dedicate a few minutes to doing some safety drills at the end of every dive.

Non-training dives are an opportunity for divers to build experience, which in turn is a prerequisite for proper SA processing and projection. However, while many divers are proud of the number of logged dives they have accumulated, this number doesn’t necessarily reflect a diver’s true experience: a thousand dives in the same lake near your home town doesn’t give you the skills to dive a wreck in the North Atlantic. Genuine experience is built by diving frequently and repeatedly in a variety of environments, each of them with different hazards and challenges such as entry and exit, currents, temperature, visibility, depth, etc. The more varied and profound a diver’s experience, the more likely this diver will be able to relate their perceptions to a known scenario and quickly select the proper response.

However, repetitive experience by itself does not lead to an accurate reading of a situation. By way of illustration, in his Allegory of the Cave, the ancient Greek philospher Plato describes a group of people who have lived all their lives chained to the wall of a cave. The people watch shadows projected on the wall from objects passing in front of a fire behind them and give names to these shadows. The shadows are the prisoners’ reality, but they are not accurate representations of the real world – they represent the fragment of reality that we can normally perceive through our senses. The same objects under the sun represent true reality, which we can only perceive through reason. Without education, even extensive experience leads to a distorted perception of reality. Applied to a diver’s Situation Awareness, distorted perception caused by a lack of education leads to distortions in processing and projection, with potentially hazardous outcomes.

There are two types of factors that can jeopardise a diver’s SA, foundational and contextual. Foundational distortion relates to the prisoners in Plato’s allegory. Despite repeated experience, the lack of education keeps a diver in a state of wrong perception and fear to experience anything else. Diving a single tank of air to sixty meters and beyond with unplanned decompression is an example. In some areas, this might be perceived as a ‘normal’ dive permitted by local regulations, without any recognition, interpretation, evaluation of the risks involved. The absence of understanding of the actual hazards leads to faulty projections and bad decisions.

Contextual distortion describes a temporary effects where situational factors like stress, mental workload, fatigue, or complexity may affect a diver’s state of mind and lead to human errors and accidents. The benefit of diving as a team (as defined in a prior article in the ‘House of Cards’ series) is to mitigate individual contextual distortion by adding redundancy to the analysis of the situation – i.e., extra brains. Beyond individual SA, it is therefore important to develop a shared SA within the dive team. Moreover, different people vary in their ability to acquire SA, and providing the same training will not result in the same SA across different individuals with different sensibility and sense-making capabilities. The degree to which each team member possesses the SA required to meet their responsibilities in the dive plan determines the success or failure of the mission. To plan a dive optimally, it is necessary to identify each team member’s strengths and weaknesses and assign roles accordingly.

A post-dive debrief is essential for developing a common understanding and improve the team’s collective Situation Awareness. In the debrief, each team member contributes their own interpretation of various situations during the dive and the subsequent decision making processes, and analysis the dive’s ultimate success or lack thereof.

Situation Awareness is the apex of our House of Cards of diving foundationals – the ace card. In military aviation, the ‘Ace Factor’ describes the ability to keep track of everything going on in an immediate environment during airborne combat. While diving is a more pacifist endeavour in most cases, the divers’ Situational Awareness, both as individuals and as a team, is what makes the difference between looking and visualising, between being reactive and being proactive, and between being a victim and being a survivor. To quote Sheck Exley, “Survival depends on being able to suppress anxiety and replace it with calm, clear, quick and correct reasoning”.

About the Author

Audrey Cudel is a cave explorer and technical diving instructor specialising in sidemount and cave diving training in Europe and Mexico.

She is also renowned in the industry for her underwater photography portraying deep technical divers and cave divers. Her work has appeared in various magazines such as Wetnotes, Octopus, Plongeur International, Perfect Diver, Times of Malta, and SDI/TDI and DAN (Divers Alert Network) publications.