Making the Jump on the HMS Southwold

One of Malta’s Historic WWll Wrecks

Malta, at last. This trip had been in the planning for a while but kept getting postponed for lack of time and other reasons. When I was invited to represent Divesoft at Rebreather Forum 4 in April 2023, it was an ideal opportunity.

Together with my buddy Willem, we set out to dive some of the deeper wrecks off the Maltese coast, including the beautiful HMS Southwold, a British WWII destroyer. The wreck lies in two sections. The bow section is the larger piece. It is about 40 meters long and lies at a depth of almost 68 meters, entirely on the starboard side. The stern is about 30 meters long and sits at 74 meters, upright on the seabed. The distance between the now and the stern section is about 200 meters, which means you have to do at least two dives to see this wreck in its entirety.

The History of the Southwold

The HMS Southwold was ordered on 20 December 1939. She was built by J. Samuel White and Company of East Cowes as part of a 1939 emergency program. Her keel was laid on 18 June 1940 with job number J6274, and the ship was launched on 25 May of the following year. The vessel was completed on 9 October 1941.

HMS Southwold was a Hunt class destroyer, 86 meters long, with a beam of 9.5 meters and a net tonnage of 1050 tonnes. These ships had a top speed of 25 knots and were designed for convoy escort. HMS Southwold had a crew of 168 and was armed with three twin-barrel 4-inch MK XVI guns, one on the bow and two in the aft section. She also carried anti-aircraft guns and anti-submarine depth charges.

Upon completion, the Southwold went to Scapa Flow for trials, after which she joined the Mediterranean fleet. Between February 12 and 16 of 1942, the HMS Southwold was part of the escort for convoy MW9B. The convoy failed. Of its three merchant ships, one was damaged and made it to Tobruk, but the other two sank. The Southwold and the other escorts returned to Alexandria. A few weeks later, on March 20, the HMS Southwold left Alexandria to be part of convoy MW10 to Malta, under the command of Rear Admiral Philip Vian. During the 820-mile voyage to Malta, the convoy came under heavy attack.

Once the Southwold and her convoy were located by the enemy, their presence was reported to the Italian navy. On 22 March 1942, the Italians sent ten ships to intercept the convoy in the Gulf of Sirte (Sidra), 150 miles northwest of Benghazi. Vian had one four cruisers, one anti-aircraft destroyer, and 17 destroyers to protect four merchant vessels. However, Italian commander Admiral Angelo Iachino had the 15-inch guns of the battleship Littorio and the 8-inch guns of his cruisers at his disposal, against the 6-inch and 4-inch guns of the lighter armed British vessels. Admiral Vian was outgunned.

For defense, the British laid a smoke screen to prevent the Italians from ranging in on them. They then began a series of quick sorties, launching damaging salvos at their superior opponents and retreating back into the smoke before the Italians could find their range.

The morning’s fighting was inconclusive, but the Italian squadron approached again in the afternoon. This time, Rear Admiral Vian closed the range to below 10,000 meters, emerging from the smoke screen with a salvo against the Littorio before the heavy fire from the battleship’s guns forced the destroyers to retreat. The Italians retaliated, hitting and severely damaging the cruiser Cleopatra.

After one more exchange of fire, the Italians withdrew their ships as night approached and their lack of radar would have put them at a disadvantage. The battle went down in history as the Second Battle of Sirte and is generally regarded as a British defensive success against a superior force. However, the convoy did not fare so well.

The next day, March 23, German aircraft took over the attack to prevent the convoy from reaching Malta. Only 20 miles from the Maltese coast, the Germans sunk the Clan Campbell. Another one of the merchant ships in this convoy, the Breconshire, was hit by enemy bombs and came to a halt a few miles off St Thomas Bay. The weather turned rough, and the Breconshire drifted helplessly towards shore. The crew managed to anchor 1.5 miles off Zonqor Point.

The next morning, 24 March 1942, the Breconshire was dragging its anchors over the sandy bottom, pushed by the current. The Southwold was ordered to tow the Breconshire. While attempting to pass a line to the disabled merchant ship, HMS Southwold ran onto a British mine and was hit near the engine room. One officer and four sailors were killed. All power and electrical supplies failed, and the engine room was flooded.

The crew managed to start the diesel generator and stop further flooding by shoring up the bulkheads and plugging leaks. The tug Ancient was sent to tow the Southwold to safety, but it was too late: The ship’s side plating next to the engine room split on both sides all the way up to the upper deck. The Southwold listed to starboard and began to sink. The amidships gradually sank lower, and the destroyer began to fall into the swell. She was then abandoned and eventually sank in two separate parts. Her injured crew members had been transferred to the destroyer Dulverton.

Diving the Wreck

To get to the Southwold, we used the services of Cpt. Jason Fenech. His boat Delfino is a traditional Maltese vessel, fully equipped for technical diving. Jason’s knowledge of the wrecks is vast. He has no trouble locating even the deeper ones, and, most importantly, he always drops the shot line in the right place, at the right time.

We were helped by deckhand Karsten Kuhl, who also served as the support diver. This job is important: If something were to go wrong during the dive, Karsten was prepared to jump into the water with extra tanks.

Our plan was to dive the bow of the Southwold. I was diving with my regular buddy Wim using my Divesoft Liberty sidemount CCR. On the captain’s signal, Wim and I jumped into the water and let the current take us to the shotline. Once there, we signaled to each other to begin the descent. I went first, followed by Wim.

After three minutes of descending, we arrived at the wreck and immediately proceeded to the rear of the broken-off bow section. We looked inside and did a lap around the section. As planned, Wim deployed some lights so that the wreckage was backlit. What a tremendously beautiful wreck the Southwold is. We found a few empty shells, and a twin-barreled cannon caught our eye, still standing out proudly after many decades on the bottom of the ocean.

With a planned bottom time of 35 minutes, our dive wasn’t that long. But before we had to start our ascent along the shot line with 90 minutes of mandatory decompression stops, I still had time to take a few photos of the prow, lit up nicely from the side by Wim. Satisfied with some great photos, we thumbed the dive.

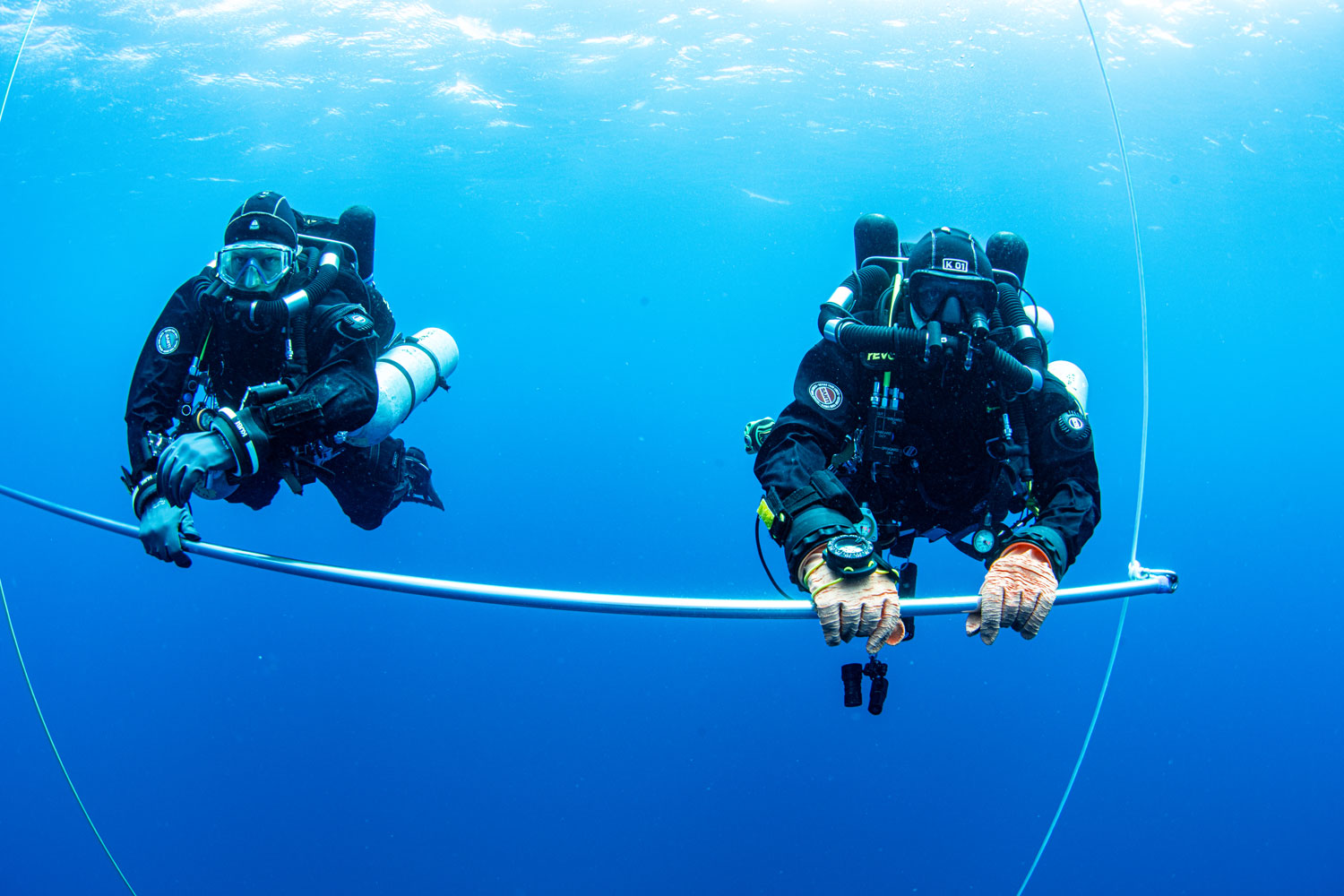

For optimal safety during decompression, we used a deco station. The last diver had the task of disconnecting the deco station from the shot line so that we could do decompression together. The captain only had to keep an eye on a couple of red buoys, instead of tracking several DSMBs in different places.

Having a deco station is also very convenient and relaxing for the divers, as it provides an easy reference for maintaining depth. For added safety, our station had spare cylinders attached to it, to be used in the event of a gas problem.

After completing our final stop, we emerged smiling from ear to ear and were received by Jason, who had come astern to greet us. Karsten lowered the lifting platform, so that we had no trouble getting back on the boat with our rebreathers and bailout bottles.

Happy as two children, we can tick the HMS Southwold off our to-do list.

About the author

Kurt Storms is a member of the Belgian military, an underwater cave explorer, and an active technical /cave/rebreather diving instructor for IANTD. He is also an ambassador for Divesoft and Ursuit. He started his dive career in Egypt on vacation, and the passion for diving never ended. Kurt is also founder and CEO of Descent Technical Diving. He dives several CCRs such as AP Diving, SF2, and Divesoft Liberty SM. Kurt is also one of the push-divers documenting a new slate mine in Belgium (Laplet). This project was news on Belgium Nationale TV. Most of his dives are mine and cave dives. In his own personal diving, Kurt’s interests are deep extended-range cave dives. His wife (Caroline) is also an enthusiastic cave diver. In his free time, he explores Belgium’s slate mines, and often takes his camera with him to document the dives.