Dive stories

A Behind The Scenes Look Into The Making of “Close Calls”

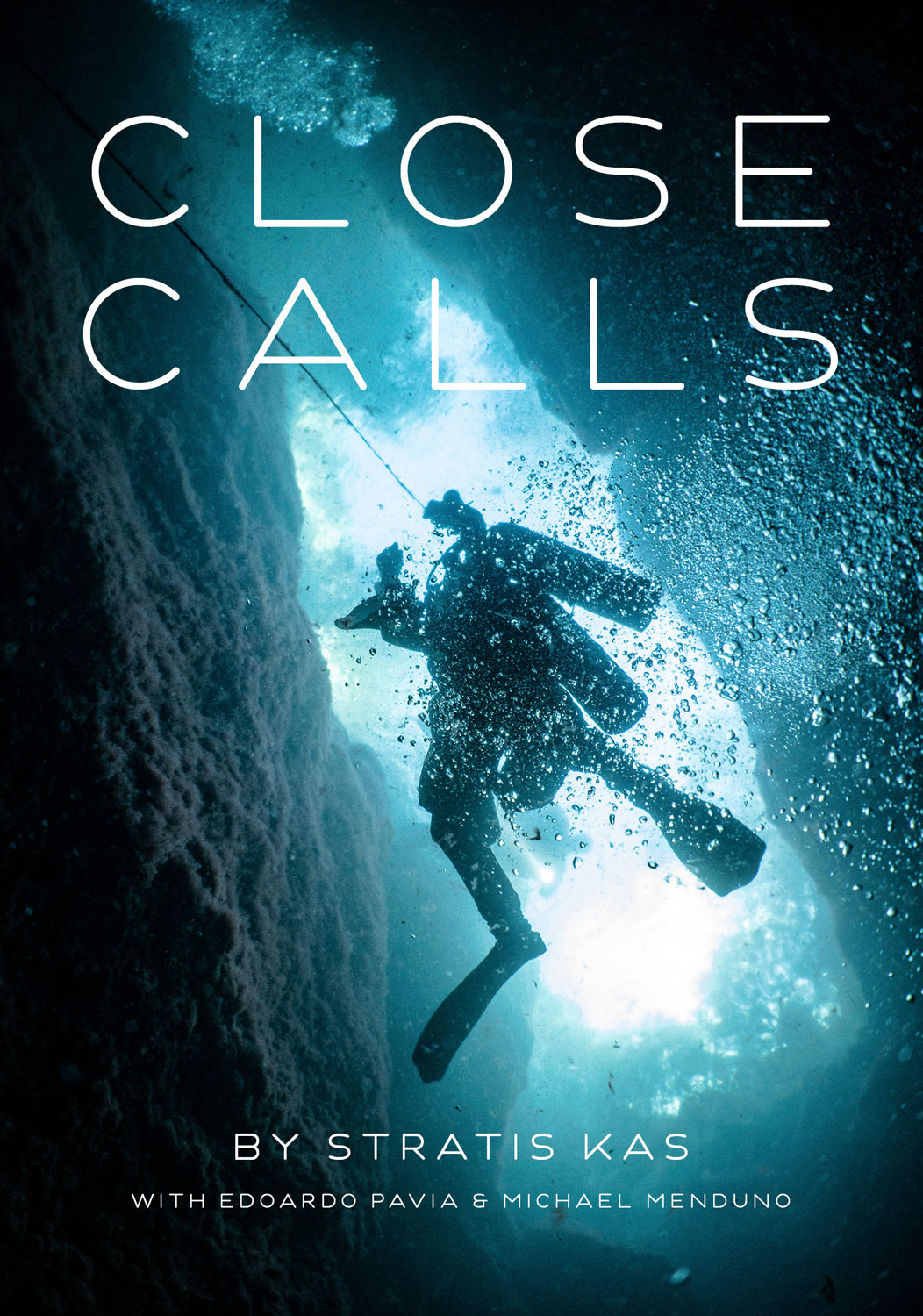

Greek cave diving instructor and adventure filmmaker Stratis Kas has released his much-anticipated book “Close Calls,” which is a collection of 68 gripping, personal stories by high profile technical divers about diving incidents that nearly cost them their lives. Contributors include divers such as Phil Short, Luigi Casati, JP Bresser, Thorsten Walde, Cristina Zenato and many more. You won’t want to put it down.

“My intent was simple,” Kas explained. “If high profile divers and dive industry leaders were willing to share their own mistakes and lapses of judgement, many of which nearly cost them everything, it would help rank-and-file divers realise that they are fallible and susceptible to making similar errors, and hopefully make them safer divers.”

The 366-page, print-on-demand book, which is arguably a must-read for every diver who is serious about their safety, is available at Kas’s website as well as Amazon and other resellers for €40. What’s more, fifty-percent of the profits will be donated to DAN Europe’s Claudius Obermaier Fund, a charitable fund that helps divers in need.

Italian explorer Edoardo Pavia, who contributed his own close call story, assisted Kas with the project. I also contributed a story, helped with the editing of the book and wrote the foreword. So, I thought it might be fun and insightful to talk with my fellow contributors about making the book.

Here’s how it came out.

Alert Diver: Maybe starting out, how do you two know each other? How far back does your association go?

Stratis Kas: May I start?

Sure.

Stratis (SK): Well, Edoardo has been on my radar since I was a young diver. He’s been one of my inspirations. Not a mentor, because we didn't know each other, but he was a person I looked up to. I looked up to the things he was doing. I met him for the first time at the 2018 EUROTEK in the UK, and I was charmed by his personality, how calm he is, how Zen he is and how comfortable it is to be around him, which is not typical in the diving industry. Then again, perhaps it’s because we are both Italian. I am part Italian. In any event, Edoardo remains one of my heroes, but I don’t tell him that very often anymore. That's the story.

Edoardo, what do you have to say for yourself?

Edoardo Pavia (EP): I've never met this person before [Laughs]. Stratis is obviously younger than me, and speaks Italian like an Italian. In fact, he speaks many languages. We have a famous saying in Italy, “Una Faccia Una Razza.” It means one face, one race. There is a link between Italy and Greece that is not written anywhere but we feel that we are sharing the same land, the same story. You are more intimate when you can share a language together. Yes, we met at EUROTEK and started to share stories. And after that we found out that we shared the same passion. And so that's how everything started. Stratis and I are good friends.

The rest, as they say, is history. Stratis, I want to ask you about your original motivation for the book, but before I do, I’d like to ask Edoardo—how did you get involved?

EP: Well, Stratis is a very generous person. This is the truth, and it must be stated more than once: Stratis did nearly everything. The entire job and the entire idea and project belong to Stratis. Stratis has kindly invited me to be along with him. And I think that the great value of this project, apart from the friendship that we share, and I'm very grateful to him for this invitation to be part of it, I think he had a great vision of this book.

As I read through it, what comes up is that the idea is simple and straightforward, but it’s complex at the same time because of the depth of the stories. I think it's a delightful project, and I'm sure the book will be a success, which is what Stratis deserves.

Stratis, how long has this project been in the works? When did you get the idea and start moving toward it?

ST: Well, as I mentioned in the book’s preface, the idea came to me at EUROTEK. Interestingly, Edoardo was indirectly connected to the idea though he didn't know it at the time. At EUROTEK I spoke with Luigi Casati, the Italian cave diving explorer who is a very good friend of Edoardo.

Luigi explained to me that he was planning to speak and expose all of the mistakes he had made while diving. He shared a couple of stories with me, and I was really impressed. I felt that stories like that should not be kept secret, though there was a tendency for people to do that. In my case for example, I had had a frightening incident in my early cave diving years, but I didn’t want to scare my family. I also wanted to forget about it. Anyone who has lived through a near death experience knows it is so terrifying, especially if the experience lasted for a while.

If you cross a red light and suddenly a truck rushes past behind you, it’s done and finished. But if the experience lasted 30-40 minutes and you suffered through it thinking you were going to die, well for me, I wanted to forget it completely, and did my best to do that. But when Luigi explained to me what he wanted to do I was inspired because his story was ten times more impressive than mine, ten times more difficult to survive. The idea stayed in the back of my mind until I met Edoardo the next year at BALTICTECH in Poland.

What year was that BALTICTECH conference?

SK: 2019. Ironically Edoardo had helped translate Luigi’s talk into English. So, he was already involved in this concept of sharing mistakes that had inspired me, without even knowing it.

Serendipity!

SK: We met at BALTICTECH and I discussed the idea, and at some point I said to him, “Why don’t we do this project? Why don’t we make a book about it?” Edoardo was very enthusiastic about it, so that’s what we did.

What would you two say have been the biggest challenges in putting the book together?

SK: The biggest challenge for me? I figured that everyone was in lockdown as a result of the pandemic and had plenty of time on their hands, so it would be easy to get the stories. I initially gave people two months to complete their stories. I planned to wrap everything up by May 5, but that became May 30, then June 5, June 30, July 15, July 30, and then the first of September. [Chuckles]. In fact, we got the last few contributions in 10 days ago [in November].

That was the biggest challenge; getting people who were important to the book to say ‘yes,’ they would do it, and then to figure out how to cajole them into getting their stories done. Once we had the material, well, it took us two months to do the editing, and another week for color proofing. These were the tasks that the divers in the book probably aren’t aware of.

Some of the people I reached out to took a long time to reply, and some didn't get back to me at all. And when it was someone whom I really wanted in the book, it was frustrating because I couldn’t let it go. It was like having a girlfriend who you really like, but she doesn't call you back. And all your friends say, she doesn't like you. And you are like, I'm going to give it another weekend. Just another weekend. And then on Monday morning she calls you and tells you she's going away for the week, and you're like, Okay, one more weekend. Because you care. I cared because I felt it was important to have some of these people in the book. Long story short, some of the waiting times were impressive.

And there are still a few divers out there who didn't call you back, right?

SK: Yes. Some of them didn't. Amazingly, in the very beginning, about 90% of the divers who didn’t want to participate in the book were GUE (Global Underwater Explorer) divers, and their answers were always the same: “They never had a close call.”

Ha! That’s the GUE way: no drama, if you can avoid it!

SK: Fortunately, after a while that pattern started to break, and I was able to fill out the roster.

I get it. Of course, there are a number of GUE people in the book. If you’re around long enough, something is likely to go wrong. That’s the point, right?

SK: That’s correct, yes.

EP: I'd like to say something about waiting for that person who's not calling you back. Written communication, whether text, message or email, is a delicate way of communicating between one another. So, I try to not judge or jump to a final conclusion if I don’t hear from someone. Sometimes people are just living their life. We don’t know if they are having troubles, or are in pain, or are just a bunch of [expletive]. Nonetheless I do understand Stratis’ frustration on this project.

Fortunately, it is easy for people to understand the purpose of this book, which is a good thing. In fact, I happen to know that Stratis ordered a Porsche recently because he knows that this book will make him a fortune. And Michael, you have been writing and editing all your life, so you know, there’s a huge amount of money to be made with this kind of work.

Ha! Exactly! It’s right from the old adage, “How do you make a small fortune in diving? Start with a big one!” Stratis’ must have been pretty big.

Let me ask you both, was it difficult for you to share your story, your mistakes, in the book? And how about others? Do you think it was difficult for some of the people who contributed to be vulnerable and say that they made a mistake?

SK: For me it was not difficult at all, it was actually kind of a relief that I was able to finally share it. I did share it with friends who weren’t divers, but they didn't get it. Others found the idea of being in an underwater cave completely terrifying, regardless of being lost or not. So, for me it was a really big relief.

The people who shared their story did it very openly. It was actually quite impressive. You can imagine from their credentials, especially for instructors, that it would be hard for them to admit to making mistakes, for example, having one of the students they were supervising, run out of gas during a class.

Photo by Stu Gardiner

We have one of those stories in the book. Yes.

SK: The stories are generally impressive, and the story tellers accept the blame; they don’t blame the equipment, or anything else. They got the message.

Edoardo, how about you?

EP: To answer your question, like Stratis, I felt that I had nothing to lose, I could only gain by sharing my experience. Ironically, during the lockdown, I took an online course on Human Factors with Gareth Lock. After the course, I really understood the value of sharing. Because we all make mistakes; there is no way to avoid mistakes. The course also helped me understand the difference between a mistake and a violation.

Now that I've entered what you might call the era of dinosaurs as far as diving—you know what I am talking about—I realize that there is something I can leave behind to the next generation and that is my knowledge and experience. And what exactly is that? Is it my ego saying, I have been diving here and I have been diving there? No. The truth is, the real value of my experience are my mistakes, my fears, and my errors. The next generation can get something out of that. And this I think is Stratis’ vision.

There are a lot of great divers in the book, people like Phil Short and Becky Kagan Schott. There are many names. I am not going to try and mention them all. But they are all human beings and they made mistakes. As Stratis pointed out, if these people, people like Phil or Becky can make mistakes, then what about someone like me? The fact is I have to be ready and prepare myself to accept the fact that sooner or later I will make mistakes, so I better have back up plans.

As Gareth explained in his course, the way to avoid the consequences is to be prepared, and have a system in place to catch us when we err. It applies to everything not just diving. So, I think that’s one of the reasons why it's easy to share these stupid things.

Ha! So, let me ask you two, what have you learned from making this book?

ST: What have I learned from this book? The core message is what I learned from this. The fact is that I was very pleasantly surprised and relieved that there was a lot of interest in the book. Everybody wanted to be part of it. But in this case, it's a book of all-stars, the mistakes of all-stars, and it gave me a bit more hope.

I have worried in the past, that I belonged to an industry that was very competitive and not very humble. And it is. The thing is, I am zero competitive as a person.

So, experiencing the humbleness on the part of the book’s contributors, helped me to see the other side of the industry that is closer to me. When you read their stories, you find that these divers express the same kind of passion in discussing and analyzing their mistakes, as they do when they discuss their exploration projects. That really touched me.

Edoardo, any takeaways from you?

EP: Yes,I'd like to mention two things that are important to me. The first one, as Stratis pointed out, is that this community of all-stars has responded willingly and positively. So, I feel very positive about the behavior of our diving community after reading these stories and learning about others experience. We must understand that we are strong. We have some excellent people. Yeah, there are some big egos, I’m likely the first one in line, but there are so many people, like those in the book, that add real value to the community.

I also think that the introduction of human factors and better understanding of the psychological factors involved in a dive, along with the communication potential of the web and social media, will help future generations of divers. Broad access to travel will also help them to better share and acquire knowledge. And I think that this shows very clearly.

A second thing I've learned reading these stories is that we must realize, and I'm very serious about this, that human beings are sometimes able to handle situations that may appear to be impossible to handle at first glance. Of course, it's a question of luck sometimes. Yeah, luck does help. And luck, we know, is the way of justifying our actions when things go right. But I don't think that it is just a matter of luck. There is skill. There is training. There is mental attitude, and there is respect.

You’re saying that we make our own luck!

EP: That’s right. I am always reminded of a great story about a diver friend that I have a lot of respect for. He’s not well known and not the most experienced as far as deep diving and wreck penetration. We had been working for maybe three years to locate a Mediterranean shipwreck in about 100 metres of water. We finally found the shipwreck and managed to get a vessel to take us out there. It was far from the coast and difficult to find.

We arrive on site and conditions were perfect. The sea was flat calm. I was the only one with a rebreather; the two others were on open circuit. We get ready to go in the water, and this guy has his dry suit on, and says to me, “You know what? I don't think it's a good idea for me to dive today. I don't feel I want to dive.” And he stepped back from making the dive.

Don't get me wrong, this guy dives deep. But that day he said, “No, I don't think it's a good idea. I don’t want to put the team in danger. The shipwreck will be there. Go film it and tell me what it was like.” I made the dive with the other team member, and we had some problems. When we surfaced, I told the first diver, I don’t think I would have been able to step back and call the dive after three years of hard work.

I’ve always thought that from the point of view of a diver, someone who can listen to themselves and take a step back is much stronger and more solid than divers who would always step in front of you. I confess, I have always been one of those who will say, “Yeah, yeah, let’s go diving.” So, I have even more respect for these people, and I have learned in time to do better.

That’s what I have learned from this book. That humans are capable of adapting. We are water people, and we have to be able to adapt like water to situations. I think this is something that shows clearly in the book.

Photo by François Brun

Great story. Thank you. Two last questions. Stratis you have arranged for 50% of the proceeds from the book to go to DAN Europe’s Claudius Obermaier Fund, a charitable fund that helps divers and their families who find themselves in need. How did that come about?

SK: Basically, two to three months in the project, as I started to accumulate stories, I had a number of people ask me the same question: What are you going to do with the profit? And I had no answer to that.

You mean other than buying your Porsche?

SK: [Laughs] At that moment, I felt, well, I'm actually putting together a book of other people's stories and pictures and it raised the question in me: How could we possibly share the profit of a joint project, because it is a joint project. At least I always saw it like that, and I didn’t know what to do. So, we discussed it, you were part of that, and we came up with the idea that it would be great to contribute money directly to the families of divers, who didn’t survive their close call. That’s how it came about. DAN Europe had a charitable fund like that, and they were happy to have us participate.

It seems so appropriate for this book project! Thank you Stratis.

Last question, and maybe you each can answer. What is your vision for the book? What do you hope it will do or achieve or what difference it will make in the diving world?

EP: Well, we are waiting for that call from Hollywood! [Pavia and Kas both crack big smiles]

Ah yes, the movie!

EP: We don’t have to limit ourselves. If we do, that’s what will happen. I hope that the book achieves Stratis’ first aim: to increase safety and awareness in the community, and to demonstrate that as a community, we are serious about what we do, no matter which agency we belong to, which country we are from, our language, religion, race. Our aim is to say that we love this liquid element and we want to push the boundaries as much as safely possible. There are of course some scary stories in this book. We must advise people to handle this book with care.

You don’t show it to your non-diving spouse if you are just learning to dive?

EP: [Laughs] All of the stories are short, so if you get scared, you can always jump to another story. You don’t need to read it all at once. You can pick it up and read a couple of stories, get back and read again one story that scared you more. My hope is that people will understand that Stratis has done us all a favor.

Stratis?

SK: I don't have anything to add. When the poets spoken, you shouldn't add anything.

EP: [Rolls his eyes]

SK: No, but it's true, because this is actually very much to the point. It's also nice to hear that you think of that, Edoardo.

Of course, my big, big pre-COVID dream, was to make a LIVE presentation of the book at a big event like EUROTEK or BALTICTECH, with as many of the near 70 contributors as possible. I would have them each talk a little bit about their story and discuss more in depth why it was important to them to contribute and what message they wanted to share. I think that would be beautiful moment. Not this year, maybe not next year, but at some point, it would be something good to look at.

EP: He said to me that he's looking forward to sitting at a table with a pile of books surrounded by divers saying, “Can you write ‘For John with love." That's what he's looking for. He told me that.

Michael, can I ask you a question?

Of course.

EP: Michael, you have a lot of experience. You know the divers from the past generation. You know how divers behave in the east and in the west and the stories behind them. You have been the editor of aquaCORPS magazine—the Bible of technical diving. So, I’d like to know what you thought about this project put forward by a Greek and an Italian, without being rude to the Greeks or the Italians of course.

[Laughs] Edoardo, it resonated with me immediately. Ironically, I recently compiled and republished all the fatality reports, that were originally published in my magazine aquaCORPS from the 1990s. We used to track and report on tech diving fatalities. So, when I saw the project on divers’ “close calls,” I was intrigued. It struck me immediately that information on what happened during a close call is much more valuable than a fatality report, because we have access to what was going on in the diver’s mind at the time. I immediately wanted to be a part of the project. I contributed a close call story of my own of course, and I ended up helping Stratis with editing and reaching out to people we wanted to be in the book.

This book is a study in “human factors.” I really see understanding and taking the human in the system into account as the next wave in improving diving safety. In the early days it was just blocking and tackling; making sure your gas was labeled properly, making sure you switched to the right gas at depth, making sure the equipment worked, those were the things that killed people. Those issues have been largely solved, but we still have fatalities.

“Close Calls” is a great example of what Gareth and the human factors community call “Just Culture,” a community where divers can share their mistakes and not be blamed or shamed for it. That way we can all learn from others mistakes and move forward as a community. As you both know, we are clearly not there yet, but I see this book as another step forward, and I am grateful to be a part of it.

EP: Thank you. You responded with such enthusiasm. What do you think about the possible success of the book? Is it one of those books that you would expect to find on the shelf of someone who is a diver, a technical diver.

Absolutely! I think it's going to become a classic like Sheck Exley's “Basic Cave Diving: A Blueprint for Survival,” or Lock’s “Under Pressure.” It’s a must read. There’s so much unique and important content. These are gripping, eye opening stories that divers can learn from. I encourage all of you readers to check out “Close Calls” wherever you get your books.

Thank you both. It’s been a real honor to work with both of you.

Photo by Simon Mitchell

Photo by Simon Mitchell

Contributors to Close Calls:

Aldo Ferrucci, Alessandra Figari, Alessandro Marroni, Alex Santos, Andy Torbet, Armando Ribeiro, Audrey Cudel, Beatrice Rivoira, Becky Kagan Schott, Brett Hemphill, Chris Jewell, Craig Challen, Cristina Zenato, Daniele Pontis, David Strike, Don Shirley, Doug Ebersole, Richard Harris, Ed Sorrenson, Edd Stockdale, Edoardo Pavia, Emmanuel Kuehn, Eugenio Mongelli, Evan Kovacs, Frauke Tillman, Gabriele Papparo, Gareth Lock, Garry Dallas, German Arango, Jill Heinerth, Jim Warny, Jon Kieren, Josh Bratchley, JP Bresser, Kevin Gurr, Leigh Bishop, Luigi Casati, Marissa Eckert, Mark Ellyat, Mark Powell, Matteo Ratto, Michael Menduno, Mike Young, Miko Paasi, Mrityunjaya Giri, Natalie Gibb, Nathalie Lasselin, Nuno Gomes, Pascal Bernabe, Patrick Widmann, Paul Toomer, Pete Mesley, Phil Short, Randy Thornton, Richard Stevenson, Richie Kohler, Rob Neto, Roberts Culbert & Bill Main, Sabine Kerkau, Simone Villotti, Sonia Rowley, Stefan Panis, Steve Bogaerts, Steve Davis, Steve Lewis, Thomasz Michura, Thorsten Walde , Tom Mount, Witold Hoffmann.

A collection of life-changing stories from the diving industry’s greatest, openly talking about mistakes in diving. To learn from their experiences, and improve safety. 50% of proceeds go to the Claudius Obermaier Fund, to help divers and their families in need.

Get your copy at https://stratiskas.com/closecalls/