Dive stories

A Safe Approach To Ocean Clean-up

“Every dive is a clean-up dive”. We hear this all the time, but maybe you have not yet found a safe and comfortable way to apply this approach to your own diving. In this blog, I will try to give you a few tips on how to bring trash up on every dive. I will also break the concept of cleaning into different categories, so that you can clean within safe parameters.

Every piece counts

First and foremost, I think it is important to accept the fact that we as divers cannot take on the responsibility of cleaning up everything we encounter on all dives. As heartbreaking as it is, we need to stay within our boundaries. On the other hand, I believe that every piece matters. No matter how small, if you can manage to get it out, it will make a difference to yourself and the people around you. It is not for nothing that scientists keep warning us about the immense microplastic pollution. Everything will eventually break into small pieces and enter our biology. So, if you have removed a hairband or a chocolate bar wrapper, you have reduced the amount of plastic that will turn into micro plastic. Another amazing thing about the little pieces is that divers at all levels can manage these without compromising their safety. Small pieces are light and fit into small pockets in your gear. You do need to consider whether your buoyancy skills are at a level where you are able to pick up a piece from the bottom without harming the underwater environment.

As with all underwater tasks, don’t hurry. Take your time to assess the scene. Rushing will most probably leave the place silted. Be mindful about sharp objects like glass, cans and fishing gear. And then consider if you have enough time to remove the objects within the dive plan. NDL and currents might be limiting factors.

Beware of Currents

Diving in currents can be challenging for several reasons, and staying with your buddy and a dive group is important. So, consider this if you decide to relieve the ocean from litter. Last summer, I was diving in Saltstraumen in Northern Norway. The place has some of the strongest underwater currents in the world. Unfortunately it is also full of lost fishing gear that, because of the wild tides, has become entangled in the beautiful living structures decorating the rock walls of the region. Hooks and fishing line removal in an area like this is difficult and can be dangerous, which is why I was advised to leave it be by dive guides. I consider myself quite experienced, but the danger is real. One of the local divers once got a fishing line that he had cut loose from the reef wrapped around his neck. While he was fighting this problem, the current was picking up and his air supply was running low. Only within the last bars of his tank did he manage to get loose and surface, skipping a bit of deco time he had run up. Luckily, he did not encounter any decompression illnesses afterwards. However, it’s a lesson learned when it comes to fishing lines and strong currents.

Carrying the small pieces

Most divers I meet do not carry extra gear for the small pieces they pick up. If they dive wet, they tuck it into a sleeve. In a drysuit, they use their pockets. I have nothing against these methods, but I do not think they work that well. Several manufacturers have produced mesh bags for collecting trash. The downside is that they require one hand for holding the bag. You should never have a bag like that clipped onto your gear because the bag is light and will move with the water. Once you start filling it, it will create drag, and you will not be able to see how the bag dances around your legs or if it is dragging along the bottom. Worst case, the mesh gets stuck somewhere, and now you have put yourself in trouble. This is why, when diving with a bag of this type, you should carry it in your hand, so you can drop it at any time if you encounter a safety issue. As design goes, I would go for the type of bags that have a circular and sturdy opening. They are easier to open, close and fill plus they do not have this extra piece of line in the opening, that might get stuck somewhere.

There are even smaller bags on the market that are more streamlined and attach to your upper leg. I wear a bag like this on all my dives, regardless of the equipment configurations I use, be it a single tank jacket BCD or double tanks with backplate and wing, and even when I wear stages. (I carry stages on my left side and the bag on my right thigh.) It does not interfere with the emergency gear that I have stored in my drysuit pockets.

Planning for Larger Objects

As a rule, large objects aren’t brought to the surface by random groups of recreational divers visiting a new site for the first time. This kind of thing takes planning, coordination, and the right kind of logistics. But it is always a good idea to note where you find objects and let local divers know, so that maybe they can handle the problem at a later occasion. Whenever I hear comments like, “Yeah, we know, it's been there for years” or “Nothing we can do about it…”, I challenge these kinds of statement, because there is always something we can do with the right planning.

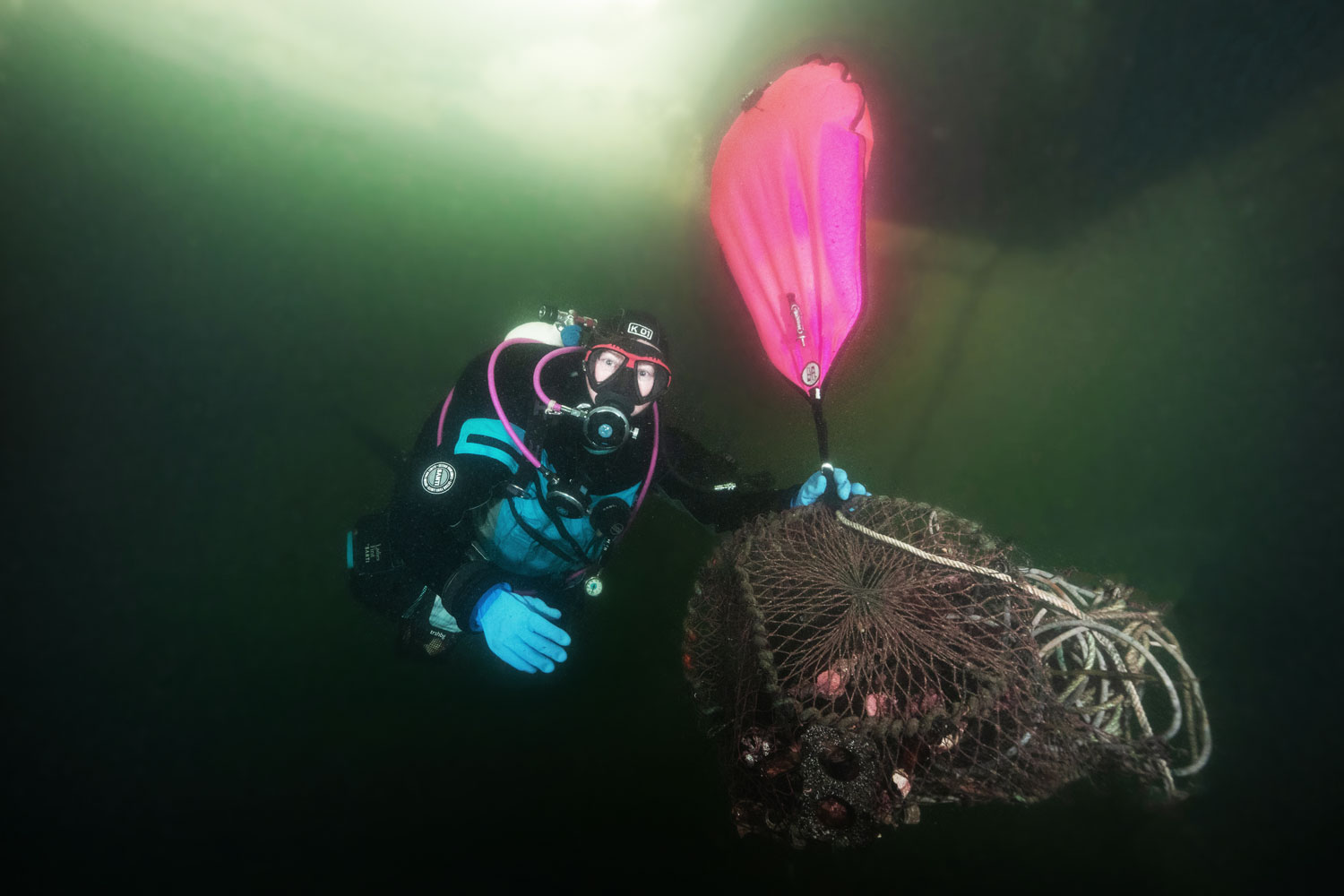

The buoyancy for lifting a large object should never come from your BCD or drysuit. If the object is too heavy, you need to bring a lift bag. Various training agencies offer courses in how to use one. If you know divers who already have that skill, join them as a support diver to watch and learn. They’ll probably appreciate your help. Discuss the plan and a back-up plan for how to conduct the job underwater. You also need to think about how to handle the object once you are at the surface. Your surface support should be as close to the location of the object as possible, so that you do not have to tow it underwater.

I sometimes participate in dives where we lift larger objects that we do not manage to get all the way back to the surface in one dive. In that case, we might tow an object a bit of the way and then park it to be picked up on a later dive.

When retrieving ghost nets, it often takes several dives to cut the net loose before it can be lifted.

These types of dives can potentially get you quite excited and should always be planned well within the NDL, since it is reasonable to expect that task loading and exertion will increase your uptake of nitrogen. DAN is planning to conduct experiments to investigate this risk in detail. It will be very interesting to see the results of this research.

Learn from the trash

This might sound stupid, but I am being serious. The more trash I pick up, the more I realise that most items are of a type that I am currently or have been using in my everyday life. When I keep seeing these items at the bottom of the ocean, it is because our trash management logistics for that item are not in place (yet). I am therefore trying to avoid or reduce my use of such products. I also try to make sure that friends and family are aware of what I am witnessing underwater. Most people seem to think that trash ends up in the ocean because an individual throws it there. I believe that is only a small part of the problem: Industry and waste management are the major players. In order to be commercially successful, industries need us to keep buying and hence wasting to a degree that even with the best waste management logistics out there, we can never keep up. At the end of the day, things turn into potential ocean waste because someone bought them, and I think we need to realise that we need to reduce our consumption.

Summary

- Every dive is a clean-up dive

- Every piece matters

- Mesh bags should never be attached to your gear but be carried in one hand for fast and easy release.

- Consider diving with streamlined extra pockets/bags that are solely used for the purpose of picking up trash

- Good buoyancy skills are needed to avoid disturbing the environment

- Be careful with what you pick up to avoid cutting and harming yourself

- Thoroughly discuss the circumstances of the dive – like currents, buddy teams, NDL – to decide whether they allow you to pick up objects

- If you plan to use a lift bag for for larger objects, make sure you have the appropriate training.

- Ask local divers for their input and make sure you have appropriate surface support

- Learn from the trash. Aside from being an ocean cleaner, can you cut down your consumption?

About the author

My name is Helene-Julie Zofia Paamand but I also named myself an underwater ambassador. I started diving in 2007 when I was living in Egypt. During my time there, I became a diving instructor, which also took me to Mexico and later the Philippines.

After teaching diving full time for 3 years, the glory of life as a dive instructor started to fade, and I felt I needed to stop while I was still passionate about the underwater World. I wanted to find different ways to bring this passion alive in others. I started underwater photography in order to share the magic I witnessed. Naturally, I also saw the flip side of modern human society and the leftovers of our privileged lives underwater. This changed what I photograph, how I dive and my lifestyle. My experiences turn into stories that I share through my photography and presentations I give at schools.

I aim to engage divers as well as non-divers towards a lifestyle that will keep our ocean healthy – not only for us, but for all the animals we share the Planet with. We have to protect what we are made of, where we come from and what we are 100% dependent on – THE OCEAN.

I still teach private courses and take courses myself to become a better and more aware diver. And all this is to widen the corps of underwater ambassadors.

Join me on Instagram: @underwaterambassador and visit my online gallery on underwaterambassador.com/